Electionomics-- Unpacking the Relationship Between Elections and Financial Markets

It’s not usually an advisor’s job to get too deeply into politics. Yet elections, like many other major cultural factors, can potentially impact markets. I can’t predict the future, but I can look to the past and present (which certainly never predict future results) as a way of understanding past context during election years.

So, I think a typical question advisors are considering at present is, “How will the 2024 election impact markets?”

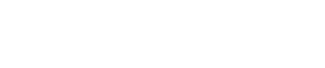

The chart below is a small snapshot of the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 results in election years dating back to 1928. It’s a little bit of a history lesson, and one that reminds us that no election happens in a vacuum. There are a whole host of external factors impacting these results beyond the elections themselves. The 2008 election year is a perfect example – the markets were generally reacting to the significant turbulence they were undergoing during what we now commonly call “the Great Recession,” than they were to a single election cycle.1

What about performance outside of presidential election years?

Although election years have typically been positive for stocks, interestingly, the best year in a four-year presidential cycle has usually been the third year, followed by year four, then year two, and finally, year one.1 This trend was first examined by Stock Trader’s Almanac creator, Yale Hirsch, in his “Presidential Election Cycle Theory.” Other scholars have expounded on the theory1, but doesn’t mean it’s a given.

Economists have several theories about these trends and why they seem to be generally true. They say the first year of a term sees a recently elected president working to fulfill campaign promises, whereas the final two years are all about campaigning and trying to strengthen the economy before voters go to the polls. 1

But again, we look to the past for context, not for predictions.

Do the markets care who wins the presidency?

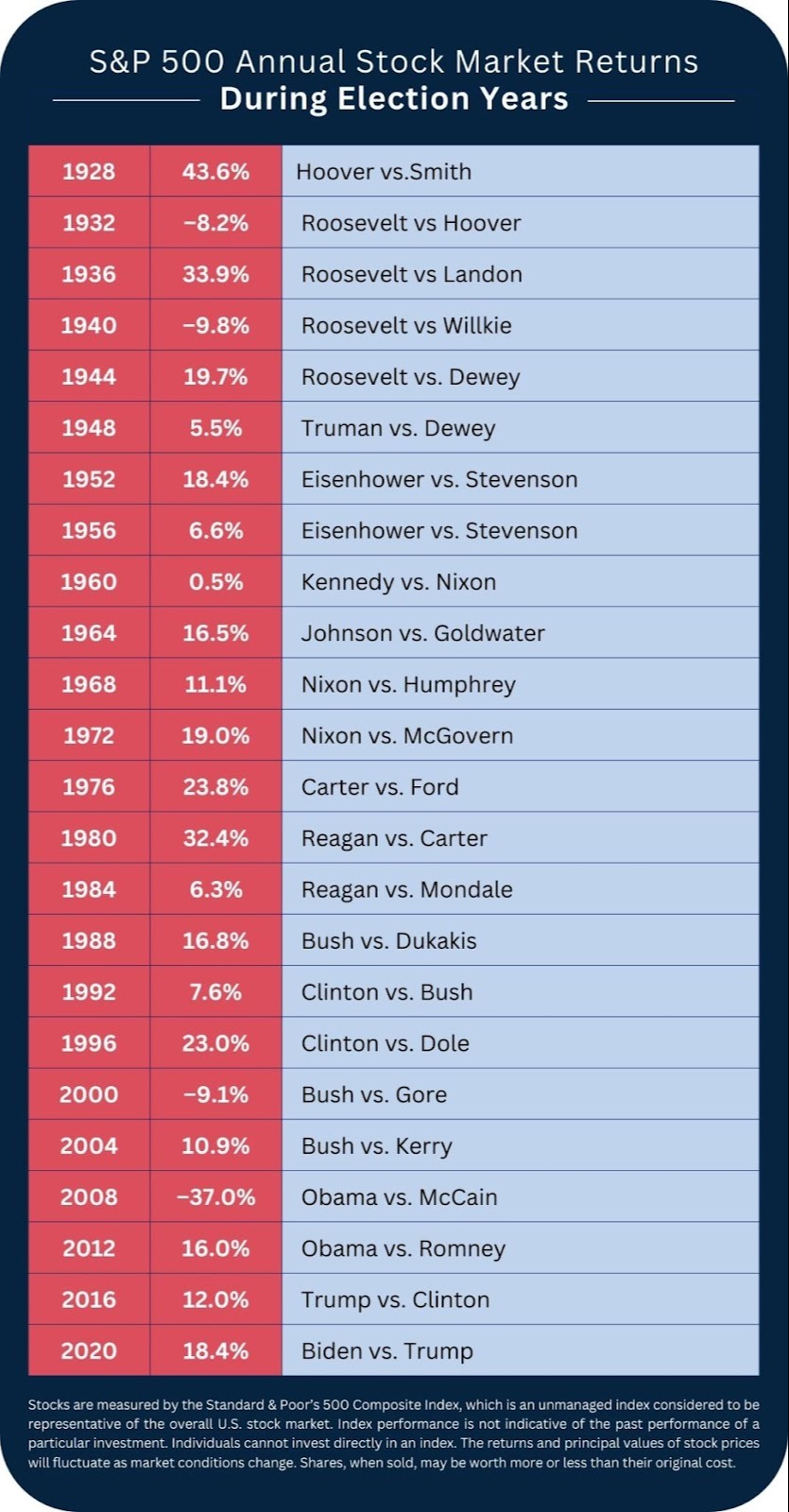

Past data tells us that what generally matters more to the markets than the elections themselves are the three months after a new president and Congress have taken office -- the makeup of the government, how it is divided between the two major parties, and the extent of that division.2 In other words, when functioning properly, the markets aren’t necessarily as myopic as some might think.

As the table below shows, Democratic control of the White House and either Republican or split control of Congress has corresponded with the most positive returns above the market’s long-term average. Conversely, Republican control of the White House and Democratic or split control of Congress has resulted in returns below the market’s long-term average.

It’s not a predictor (remember, past performance never guarantees future results), but it’s helpful historical context.

Economic and inflation trends tend to matter more than elections alone

Election results and the ways in which they correlate to the stock market over time have affected the stock market over time can be interesting to study, at least for me people like me. Still, data suggests that economic and inflation trends typically have a more consistent relationship with market performance than who wins in November.3

So what does it all mean for investors?

While it might be tempting to use events like an election to influence an investment strategy, I’d argue it’s important to take many more things into consideration, as discussed above. I’ve always believed that the best strategy is to have a well-thought-out approach to investing, a diversified portfolio, and a mix of asset classes that reflect your goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance. While there are never any guarantees to prevent loss, the above considerations are some approaches to manage risk in alignment with your goals.

Have more questions about your investment strategy? Talk to an advisor today.

1 TheBalance.com, March 13, 2022. The S&P 500 Composite Index is an unmanaged index that is considered representative of the overall U.S. stock market. Index performance is not indicative of the past performance of a particular investment. Individuals cannot invest directly in an index. The return and principal value of stock prices will fluctuate as market conditions change. And shares, when sold, may be worth more or less than their original cost.

2 Federal Reserve History, The Great Recession and Its Aftermath

3 USBank, How presidential elections affect the stock market, January 30, 2024